The full series of posts from my India trip can be read here.

Last year, when I started my new job, I received a start-up fund to use in my first eighteen months at the University, a fund which offered me some consolation for losing my title of Reader. The truth was that I didn't really care in the end if I had retained my title of Reader: my time at my last job needed to end, desperately. I had been there for over ten years and was just spinning my wheels. I took the new job and the several thousand pounds from the fund and have so far spent it on things that I wouldn't normally have money for: some sessions of coaching, a few conferences, and a trip to Sweden to visit my friend, former colleague, mentor Chris — or Swedish Chris who is now actually Swedish but had been South African and British until his citizenship came through officially killing my good joke about Swedish Chris who is not actually Swedish — last summer where we had the most impossible-to-plan series of workshops with a small group of us from several different countries, talking about learning and the war in Gaza. It was the most amazing experience of being around like-minded people without any effort, people who you could spend hours with and only want more time.

I came back from that trip wanting to go back to Sweden and called Chris in September to ask if he would be around in December for me to come and write, and he said that he was planning to be in Hyderabad, in India, actually, but I was welcome to stay in his cabin while he was gone. Hyderabad was not a place that I had known about at all until very recently. When starting up my new job, I'd taken a position on the Internationalisation Committee and Hyderabad came up in the first chaotic meeting we had, talking about the different places the University was doing work and attempting to make alliances. Within a few days, I was planning to go to India as well, with Chris and Gusztáv, his long-time friend, colleague, and confidant from Hungary. I would go to Hyderabad and run some recruitment events for the University in a hotel over the first couple of days and then Chris and Gusztáv and I would have what Chris called 'a rolling symposium' and we would visit NGOs and people he worked with when he did his PhD fieldwork there and have a full-on Lads Adventure, the exact sort of thing that I wanted to spend this money on, the sort of thing that you couldn't explain on a funding application. I knew I would get something from it, something that would influence this middle part of my career in a profound way, I just didn't know what that thing would be.

It all came together over two months, with Chris sending us messages on a WhatsApp group called 'Indian Travelling Circus and Other Adventures', links to the NGOs and people we would meet, a conference to attend, and advice about which vaccines to get, but when the time to leave on 14 November came, I was not sure I would go. My eldest daughter was having a difficult time, namely struggling to get out of the house and go to school. By the time the trip came, it had been weeks, almost two weeks, since she had gone, my phone buzzing daily with a notice that she had not attended. The Wellbeing people had called me and we'd done our best to talk through the options, but what can you really say: she's not feeling well, she's trying, but she just can't go. When she cried, it was like she was a child again to me, but I could no longer pick her up and hold her and promise her it would be okay. Instead, I sat on her bed next to her and put my arm around her and it felt like I was comforting an adult woman.

The emails with her college had been supportive, but middling, them asking her to come in for meetings and me saying that we can't right now. We didn't want to force her — she was doing her best and all we wanted was for her to do what she could do, to support her with what she wanted, and we all talked about how she has been like this her whole life and whether this time is different or not. On Wednesday, she and I got in the car and drove out to the college, just the two of us, so that she could feel it, so she could get past the parts of the trip that she says make her uncomfortable, and it was good, we got there and came back and picked up some medication.

I spent the week thinking I would cancel or cut the trip short, but no one seemed to think this was a good idea. When we said goodbye on Wednesday night we were both crying and I said I would come back immediately if she needed me. For now, I would go for a couple of days at least, to do the seminar I was going to do and then decide later if I would go to Kerala in the second week. Then it was Thursday morning and I was in the taxi and then the airport and then the plane and then in Doha. I called her and we spoke on the phone and I got on the bus out to the connecting flight, watching the fathers with babies and bags hung around their necks and remembering in my body the feeling of travelling when the kids were young.

I arrived in Hyderabad late, after two AM, on the connecting budget airline flight. An old woman was sitting in my seat on the aisle and I said to her in English, I think you're sitting in my seat, and she looked at me and then the man sitting at the window wearing a Texas Rangers hat and said something to him. He said, She would like to change seats with you, and I looked at the middle seat and thought about having to crawl over her to pee at least once, which I knew was coming, and said, No, I'm sorry, I prefer to sit on the aisle. She seemed annoyed and moved very slowly into the middle seat and the man I assumed to be her son said, Very sorry, and I felt bad, but not bad enough to take the middle seat.

We all settled in and she and the other man put their tray tables down to sleep on and were immediately told to put them back by the flight attendants. We took off and I indeed needed to pee, but when I sat down again, the man in the Rangers hat said something to me from his window seat, across the body of the old woman who was now sleeping on her tray table again, Where was I from, what was I doing, and I reciprocated, where was he from, Hyderabad but living in Dallas, oh, how did he like America, how was it with Trump, and he smiled and bobbled his head and told me the story of his American dream, his wife and his kids, who are now American. He knows they are American because they want to sleep in their own bedrooms, something he finally had to give into.

It's racist, I said, isn't it? Do you feel like everyone in Texas is racist?

And he smiled and said, Everyone is very kind, but their heart, and bobbled his head again.

He said, it happens when they, the Indians I presumed, win the Homeowners' Association (HOA) election and they (the white people, presumably) give us so much trouble, but when they win, it's fine. He talked about guns, and about health insurance and taxes and how he is a disciplinarian to his kids, how they can't deal with difficult things. We were talking over the woman who got up at various times, and the man from Texas helped her with her sandwich and food and she looked at me with disdain, before falling asleep again.

The lights went out and we landed and I made my way through the immigration queue, with the eVisa they had me print out at the airport in Birmingham which, it became clear if I hadn't done, I wouldn't have been allowed to enter the country. I waited for my bag and went out to meet my taxi driver who the WhatsApp message specified was meant to be waiting for me in a uniform with a name card, something I had secretly been looking forward to, a real feeling of opulence for a moment, but the driver wasn't there. I checked my phone and there were no new messages from the driver who had last texted at 1:40, and I had responded it would be a while as we had just landed. I called and there was no answer and then called the hotel.

Finally, the driver called and I stood outside, looking for a blue car, before seeing a man waving and realising he was saying he was wearing a blue shirt. He'd been waiting, he said, for three hours, what had happened. I said, I didn't know, I'm sorry, I just gave the flight details to the hotel, had he seen the flight details? but he said again, Three hours, and I realised what I was saying wasn't making sense to him. We drove to the hotel on the tollway and I thought about the second time I had flown into Bangkok. It had this same feeling of a new airport with a new road to it, elevated off the ground, and no longer streets packed with people the way it was the first time I went and how I'd always brought up this same story to tell people that the world had become Disneyland, that nothing was really different anymore.

The driver looked for water for me in the car and gave up at some point and I checked that we were headed in the direction of the hotel on the phone, something I had learned to do when I was in Frankfurt last year and got in a car that initially looked like a taxi, but after some time I wasn't quite sure. We were going the right way, a long highway out of the city that was pristine and clean, with flowers and plants lining it, and then progressively rougher until we hit the city and, coming off the raised highway, India, the real India appeared, even at three in the morning, people out on tuk-tuks and bikes and walking in the street. We arrived at the hotel, a beautiful glowing building, only possible as a destination for me because it was being paid for from a different budget than my startup fund, as this part of the trip had clear objectives and a schedule of events. They put my luggage through an x-ray machine and as I came into the lobby, a man slightly older than me smiled and called me over to check-in.

It was four now, and while signing through forms, the concierge offered me a small bottle of water which I drank quickly and he said, Do you want another? and I said, No, that's okay, and he said, Are you sure? holding one up to offer me.

I said, Oh thanks, I haven't drank anything since Doha, which concerned him.

Wasn't there any water in the taxi?

I said, I think there was supposed to be, but it all went a bit wrong, the guy wasn't waiting for me, I had to call and–

As I was saying this, he stopped writing and looked concerned and said to the other man working at the counter, Who did this pickup?

The other man looked at a list and said, Shiva?

And the first man was annoyed, Shiva? Shiva, they are all called Shiva, which Shiva? and then to me, I'm very sorry, sir, this shouldn't have happened, I will get to the bottom of it.

Oh, I said, no, no, it's fine, it's just– no, it's fine.

And he said, No, sir, I am very sorry, sir. Very sorry.

The conversation turn closed and he gave me my key, the eleventh floor, facing the city, very good light, he said, Breakfast in the morning from six until ten-thirty. And I thanked him and went up to my room.

I woke up sometime later, in the morning, feeling okay and went to breakfast, the five-star hotel breakfast with everything you could want, but allergy labels on almost everything that said dairy and I slowly started to realise that there would be ghee in everything, that at some point it would be unavoidable, but I decided to press on in the hotel at least, to avoid it there and see what would happen on the rest of the trip. There was a treadmill in the hotel gym and I went up to run for a while and then showered and set out looking for a bank.

When you travel, you make analogies to understand places: Laos is communist Thailand. Canada is a polite America. Korea is Japan with the plastic wrap taken off. India, on the first day in India, felt like Malaysia without the tension. I was the only white person as I walked on the road, but I didn't feel people staring and no one was calling out to sell me things. A man did try to engage me as I went down a road and as I came back up not finding the bank I was looking for, I asked, Where's the bank? and he pointed and then said, Selfie?! and had his friend take a picture of us. He thanked me and I went to leave, and the friend said, Selfie, and gave his phone to the other guy, who took a picture of us shaking hands.

Like Malaysia, you need to give up on your sense of road safety in India. You cross the road, and you just go, and just make eye contact and you probably won't get hurt. You're tempted to think that it must be safer than it appears, but I remember how many people died in Malaysia, how often you would see people dying: not often, but often enough. And then of course I got more comfortable because this is the way the world actually is, this is reality: the cars always missing you and the ATM not where you thought it would be but some place that seems strange to you, in the car park for some reason rather than the actual building. I walked up to the mall where my vegan app told me I would find food and I ate alone, staring at my phone.

On Saturday, I got up before six and ran in the hotel gym sat on the top of the hotel and looking out over the city. I dressed and decided to walk to the conference where Chris and Gusztáv were presenting, the way that I had walked the night before and which seemed safe enough and not too hot. People were walking on the road, but almost no white people. I walked past all the hawkers and stalls serving curries and sundries and people getting on with their lives. The conference venue was called the T-Hub, a huge building among other huge buildings in what was another business centre it seemed, and I arrived without sweating much. I found the check-in table around the back of the building and was putting my things in my bag when I saw Gusztáv behind me. We hugged and he said Chris was up on the fifth floor.

Gusztáv, like many of Chris's friends I’ve heard about over the years, was a kind of legend in my mind, a Sociologist interested in rural development, short supply chains, food security, and small-scale farmers. Chris would talk about him when Chris led doctoral workshops, about how Gusztáv had a kind of preternatural curiosity. They had met just because they started talking at a conference, when they both were skipping a session, or that's what I remember about it at least. Gusztáv is Hungarian and back in my 2008 mindset when I was Chris's student and Gusztáv appeared in stories, I could see him wearing a felt hat like the one Chris wore, a kind of generous soul from the mountains. I don't think I had ever met Gusztáv before, but l couldn't be sure: Chris and I have talked deep into so many nights that his stories about travelling in Hungary, about Gusztáv's sailing buddies, about Gusztáv's kids and wife, and their projects together all felt like I had experienced them myself, so much so that seeing Gusztáv felt like seeing a long lost brother for the first time: I recognised him, yes from pictures, but also because I knew him already, the way Chris is an animating electric current in relationships between people all around the world, people you have never met, but when you do, you will hug them and you will suddenly be friends.

I went up and into the main conference room and there was Chris with a beard, trying to sort something out and we hugged. Eventually, Gusztáv came up too and we talked about our experience, but Chris was distracted, something was happening at home and he wasn't sure what to do. We caught up a bit and Chris went off to do some work and take some calls and then we found their presentation room up on a different floor of the building. The three of us went up and sat down together and started chatting about everything as we watched the Indian AV people and a young man in a beret who it turned out was leading the session tried to get things ready.

The conference presentation had been the basis for Chris and Gusztáv's trip, but their session, which seemed to be mostly oriented towards business people talking about AI, ended up being for PhD students and oddly, instead of speaking in person, they played seven-minute videos of all of them presenting, followed by two professors making comments on them, not at all what anyone expected, but as it ended they shrugged. Welcome to India.

Chris disappeared and came back more distraught, things had gotten worse and he needed to go to the UK as soon as possible. Gusztáv and I stood trying to help or comfort or do something, but there was nothing to do or say. He left to take a few more calls, and send some emails, and I went down to have lunch, curry and roti and realised then I, the strict vegan, was going to have to take a liberal approach to ghee, the butter that everything was fried in, if this trip was going to be manageable in any real way. Then Gusztáv came down and got his food and we walked around the building into the sun, and tried to find a ledge to sit on and eat and catch up. We talked about Chris and our relationships with him over the years, and our marriages and families. And then on to the more serious conversation, what we would do if he had to leave — we both had done none of the planning, had just bought the plane tickets when we were told, milestones on the trip that we knew we would need to hit. I said I would think about going back early, I had been thinking the same thing anyway because of my own problems at home, but Gusztáv said he would go on regardless and I knew I wanted to as well.

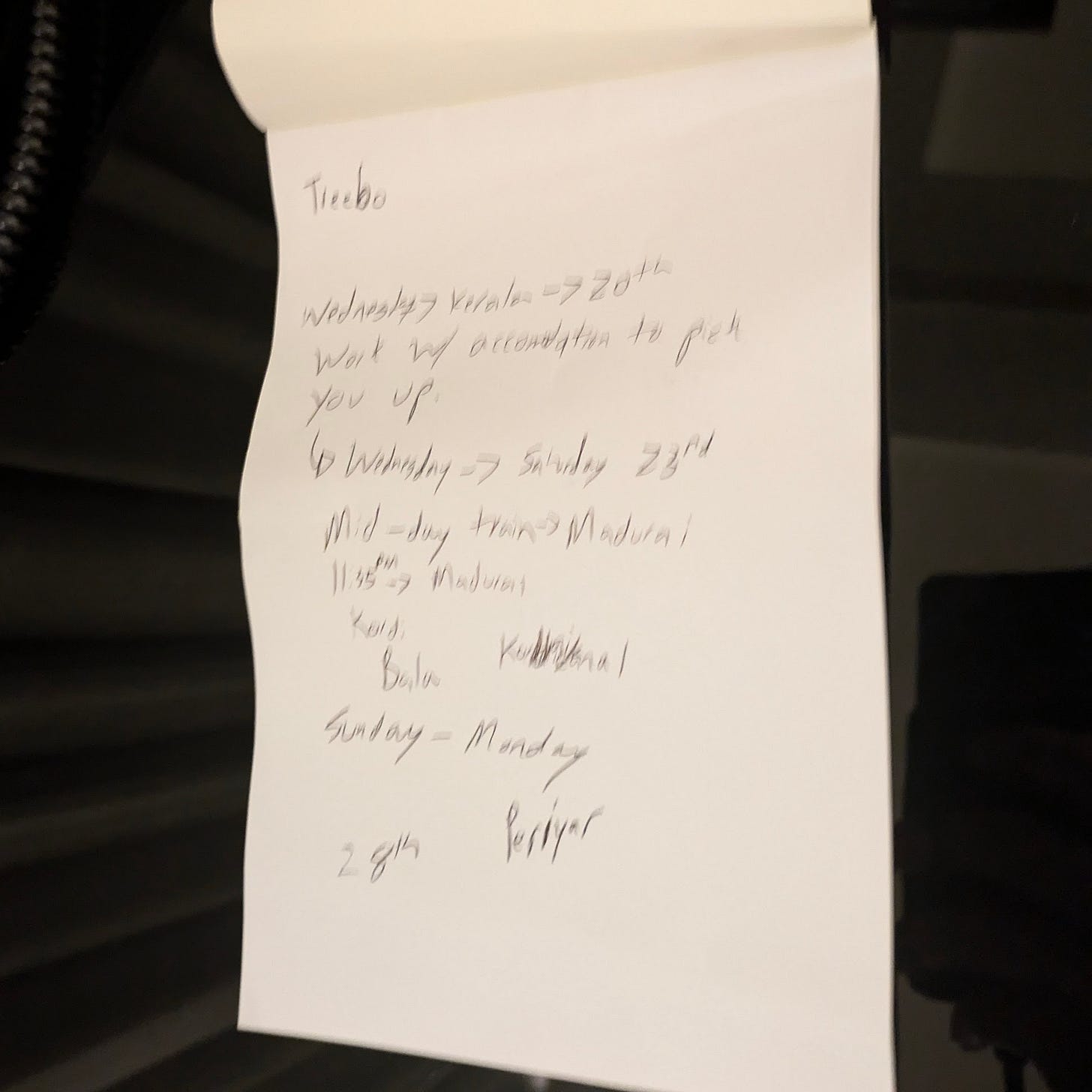

Chris came down and said he would be leaving at nine that night and he had notes for us, what we would need to do and where to go and whom to call, very rough single words and names, Bala, the man who would meet us in Madurai would take care of everything at some point. Chris was upset though and as we talked, calls came, appearances by people from his life that we had talked about for years and years and we sat on a little ledge, Gusztáv between me and Chris and I realised if we were three brothers I was the youngest one, a little boy compared to these actual men. Chris sat on his computer inside for a bit while Gusztáv and I attended a few more sessions and we had an impromptu meeting with an educational start-up from Singapore, and then it was time for both of them to go. They called a tuk-tuk and I hugged Chris goodbye and then Gusztáv and said I would see him on Monday when we could make a plan and they were gone.

Hi Stephen,

Thanks for being my/our bard on this unforgettable journey... I look forward to reading our story through your glasses... (literally :))

Gusztáv